Donald Sutherland's Gated Tears in Pride and Prejudice (2005)

What It Means To Process a Necessary and Joyful Loss

Words are the foundation. Donald Sutherland told Variety in 2006 that “[I’ve] built my life through words…I’ve used other people’s words as a guide—skeletons of reality that I can expose with my flesh and blood and imagination.” The words are the skeletons and the body is formed by the performance of those words. An actor carries with them their past, marking each movement as another step in the life of both an artist and a character. And that performance is situated in a moment, where conscious choices meet the desires and conditions of an era.

The word is, of course, a beginning. It is a space for foundation and structure. Though we may make sense of the world through words, though new words bring new worlds, actors on screen beckon those words into a different fleshy reality.

How an actor uses those words across time defines a career. Sutherland has amassed nearly 200 credits as an actor, evidence of what he calls a “horizontally organized career” where “you’ve got a big plate of fruit and cheese, and you can take a piece here and there. You won’t like all of it, but you’ll like some of it.” He was the one with big ears, whose breakout role in The Dirty Dozen (1967) came when Clint Walker didn’t want to parade around and parody the stature of a military general. With this denial the director Robert Aldrich commanded the one with “big ears” to “do it.” Aldrich is one in a pantheon of monumental directors Sutherland has worked with and quietly etched his unique identity. Bernardo Bertolucci. John Sturges. Robert Redford. Euzhan Palcy. Oliver Stone. F. Gary Gray. John Frankenheimer. Nicolas Roeg. These are just some of the names that worked with Sutherland to draw a line and connect the history of Hollywood and art cinema. And then there are the three F’s: Federico Fellini (who directed Sutherland in Fellini’s Casanova [1976]), Jane Fonda (his co-star and partner for a time), and Francine Racette (his wife for nearly half a century). They were the people he loved.

And then there is the stunning, to almost any interviewer who speaks with Sutherland, lack of an Academy Award nomination. Such is the cost of a kind of ubiquity where your performances discreetly steer the direction of the film, even from the shadows. As the LA Times noted, Sutherland has “straddled the line between leading man and character actor.” The man who maneuvered through life insecure about his looks has occupied such variety that he’s been almost unplaceable. He has refused easy categorization. Unlike contemporaries like Jack Nicholson or Robert DeNiro there is little to caricature since he has no stable or identifiable type. Sutherland seems to have found a grace even in the ridiculous, carving out a niche for individuality that accompanies any slightly askew figure. In each performance he opens something up with his cavernous voice. Even as he whispers there is a sort of viscosity that carries forward a world of meaning that is perpetually open. Perhaps calming. Perhaps assuring. Perhaps alarming.

Amidst these roles Sutherland has danced around a quivering line of ambivalence. In Ordinary People he struggles as Calvin, a father dealing with the death of one son, a rumbling uneasiness in a marriage, and the guilt of survival that racks another son. Here it is not that Sutherland is unable to articulate where he stands. Rather, he seems to float between contradictory poles, ping ponging between conflicting emotions that occasionally knot together only to unfurl again. Happiness and pride are accompanied by guilt and concern.

One year before Sutherland’s Variety interview the septuagenarian appeared as the wry, proud, and loving father to that singular figure of literature Elizabeth Bennet. His performance as Mr. Bennet in Joe Wright and Deborah Moggach’s adaptation of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice showcases his ability to stand in contradictions. He is not a commanding presence, nor should he be. The performance is so quiet that Tanya Pai wrote that Sutherland "nearly disappears into the scenery” of the film. But to see the man as merely fading away, as a kind of prop where his mop of white hair hangs like a doily in the Bennet residence, is to miss him. To see him as merely adorning the towers of leather-bound books and the colorful upholstery in the messy Bennet home turns away from how much he communicates with his eyes and shifting face.

In the penultimate scene of the film Elizabeth (played by Keira Knightley) explains to her father that she loves Mr. Darcy. Taken by surprise, Mr. Bennet eventually gives his good blessing and the film nearly closes with him commenting: “if any young men come for Mary or Kitty, send them in, for I am quite at leisure.” (A line featured in the third to last chapter of the book). What might be a tense conversation that ends in some cathartic understanding and happiness is instead a wrenching revelation of what it means to give up what one holds dear.

Watch the Scene Here:

The scene begins with Elizabeth as she explains that despite what has happened in the past her father is wrong about Darcy. She does not “hate the man.” In fact, she wishes to marry him. Mr. Bennet believes, as “we all know,” that Darcy is an “unpleasant sort of fellow.” Such a judgement is to be dispensed with though if Elizabeth feels more than indifference for the man.

What unravels is the process of what it means to think one knows another person and realize you are wrong. As he listens, Sutherland’s eyebrows raise ever so slightly, as though a fear overwhelms him. He caresses his wrist with one hand, perhaps worried that another travesty has befallen the family, perhaps another marriage will come, not out of love but some material necessity.

Sutherland’s performance visualizes what it is for a father to process his daughter’s declared love alongside a concern that another faux pas, another misstep in the social decorum that dictates life, has visited itself upon the Bennets. Until now Mr. Bennet has been unconcerned with matters of propriety that determine and also are determined by class. It is not merely that the problem of propriety and money might swallow the family up, but that his daughter, Lizzie, has capitulated to the whims of society. After all, that very refusal is what binds Elizabeth and her father as much as any bloodline. The two are romantics who believe in the ideals of others informed by the stories they’ve read and the imagination they share. What scares Mr. Bennet further is that Elizabeth is there to tell him the truth about Mr. Darcy—to tell her father what Darcy “is really like” since no-one knows “what he has done.” And that fear is clear as Mr. Bennet asks, with wavering incredulity, “what has he done?”

We don’t see Elizabeth explain the details here. The film cuts to Darcy roaming outside the house. When we return the revelation has been made clear. The sun casts its glare on half of Sutherland’s face as be mutters “good lord.” It is as if the light represents a dawning realization. Sutherland is now standing (we can barely tell, framed as he is in medium close up) and his eyes are cast down. The shame that he was preoccupied with before is gone, replaced by a different shame: the shame of ignorance.

Debts must be squared. “I must pay him back,” he says, ever so gently bringing his hand to his chest, as though Darcy’s acts have struck him physically and metaphorically in the heart. How could he have so misjudged someone? Is it the heart that hurts? Is it the sudden knowledge that Darcy has aided his family too many times to count? Sutherland’s shoulders rise and fall as Elizabeth asserts “no, you mustn’t tell anyone. He wouldn’t want it.” Darcy’s desires make their way through Elizabeth, who now holds her own wishes and seeks to actualize them.

There is nothing to pay back, there is no wrong to be righted. Still, Darcy has been misjudged and that has its own kind of pain—there is to be no more.

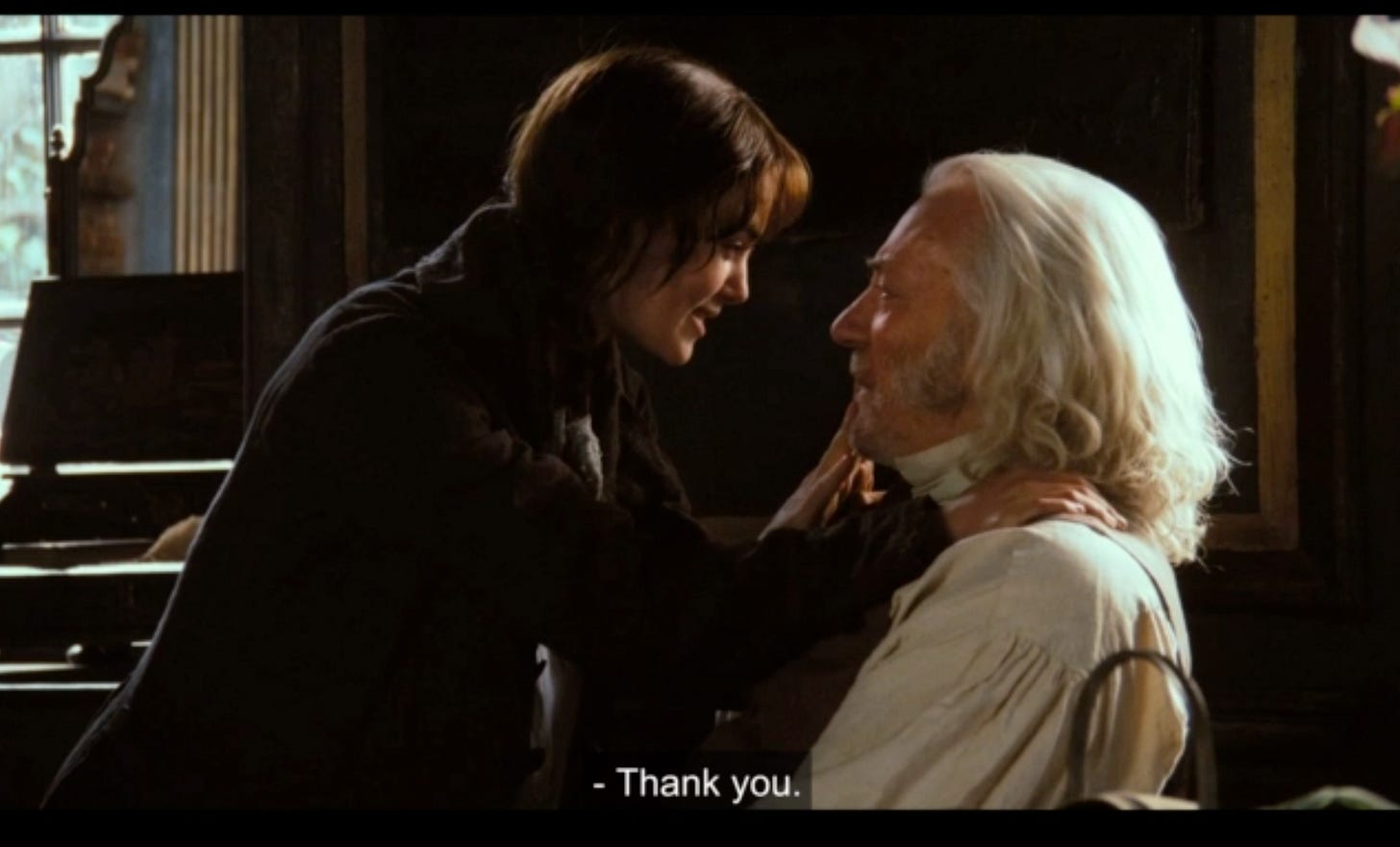

As Elizabeth explains what has happened Sutherland’s eyes don’t dart around the room in disbelief. Instead, they flutter. His hands lightly come together and his fingers kiss each other lightly as if the tickle brings him back from the pain that struck his chest. These are little movements that reveal the vertiginous experience of processing a flood of emotion. Elizabeth explains that Darcy “and I are so similar” and Sutherland looks up. There are tears trapped in the dams of his eyes. He understands what is happening. Despite the beauty of this news for Elizabeth, she does not cry, she barely struggles to let her father know, as Keira Knightley puts her hand to her mouth uttering “Papa, I…” She need not finish—the love is clear. In Mr Bennet’s monumental reckoning, crying meets longing as surprising joy entangles itself with almost-but-not-quite overwhelming sadness.

Then more little movements.

Sutherland squints. His hand, like his daughter’s, comes to his mouth. Where Knightley made a fist of joy, Sutherland leaves his palm open, as if to say, “excuse me there is too much to handle here.” The closed captions for the film read that he is: “laughing through tears.” This is something different. This is lachrymose laughter. Tears of joy and pain stay unflushed, mixing together. Nothing is moving through anything. As Sutherland brings his hand down, he finally completes the thought, offering a statement in the form of a question: “you really do love him, don’t you?”

We hear him take a breath.

Elizabeth answers “very much.”

Then a pause. As his eyes drop down there is a louder, longer sigh and a head shake. Both eyebrows go up as the tears remain locked in his eyes, gated. If we didn’t know before, we do now. The words tumble out: “I cannot believe that anyone can deserve you…”

He stops and then accepts that all too difficult thing. In the end knowing that your children will leave you never quite amounts to the feeling of watching them go. What connected Elizabeth and her father so strongly, their sense of independence in a society that required so much conformity, is now realized. Even as he knew it to be true it still hurts: Mr. Bennet will no longer be the closest person to Lizzie.

His belief only holds so much: “…but it seems I am overruled.”

Sutherland looks down again. The the acceptance hurts just as much as the fear held beforehand. He cannot reach for his chest now. To physically show such an emotional relocation would be too much. It would hurt Lizzie too much. Nevertheless, their bond is ruptured, even if that split is lined with happiness.

So he looks at the floor. Sutherland’s voice cracks and the words droop out of his mouth with little propulsion: “so, I heartily give my consent.”

The novel doesn’t portray this scene with as much sadness—Mr. Bennet’s acceptance here is brief. In Austen’s words, Mr. Bennet states: “I have given [Darcy] my consent…I now give it to you, if you are resolved on having him. But let me advise you to think better of it.” For Sutherland’s Mr. Bennet there is no space for advice. There is no guidance to be given. There is only a painful recognition.

Elizabeth hugs her father and he accepts the hug, as much in celebration as in a kind of resignation. There is gratitude in the necessary loss. It is the flickering of emotions which, as Elizabeth holds him, is made so clear by Sutherland’s stare off-screen. He cannot hide it all. Mr. Bennet has always been, if nothing else, honest. And so rather than give his full blessing he lets her go and withholds himself. The thrill and excitement is accompanied by sorrow. He holds the top of Knightley’s arms and explains “I could not have parted with my Lizzie to anyone less worthy.”

Elizabeth consoles him with a kiss on the head as Sutherland moves his hands to his lips, clasps them back together and looks down. Lizzie has left. And now he waits with the weight of a new life on the way. He shakes ever so slightly, as if all he knew would happen now courses through his body. The dam of tears will stay strong. It won’t break. “I’m quite at my leisure” he says. There will be beauty to come, but there will be loss as well.

The characters covering their mouths with their hands when they laughed was so noticeable that it made me wonder if this was supposed to be some sort of gesture that was somehow known to be a common practice in the 1800s.